St.George Russian Orthodox Church

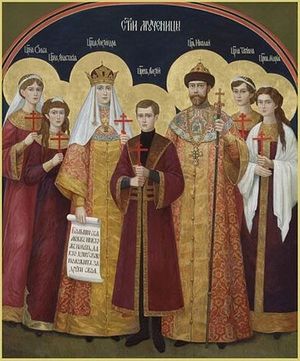

The Holy Royal Martyrs. A hundred years later. 2018

A HUNDRED YEARS LATER

Today the Tsar is with Sts. Boris and Gleb, with St. Sergius, with Blessed Ksenia, with St. Seraphim. There is neither treason nor flattery around him. He has much more power and strength.

The sovereign emperor has more power today than one hundred years ago. A hundred years ago, propaganda efforts turned him into a monster, personifying the state system, earmarked for ruthless annihilation. Cruelty, indifference, luxury, and debauchery were attributed to the regime. All of this was automatically transferred to the image of the reigning house, and so successfully that yesterday’s “loyalists” silently partook of the murder of the head of state and the whole household.

And today? Today we have been sobered by the events of the previous century. After all, we know that the luxury of the oligarchs exceeds that of the tsars at times, although wholly devoid of any moral justification. The debauchery of today’s global Sodom makes us look at many sinners of former times as at kindergarten students. And the indifference of people to one another in a world where money is the main value is unmatched. As for cruelty, the twentieth century surpassed all. The tongue goes numb here and fingers refuse to type.

The Tsar rises above the age-old lies, appearing before our contemporaries in his human greatness and martyric crown. The question is not in the restoration of the monarchy, but first in the awareness of our past and the improvement of the present. Now, love for the last Tsar is easier and more explainable than at the beginning of the previous century during the treason of some, the indifference of others, and the demonic hatred of others. If at that time he was surrounded by “betrayal, cowardice, and deception,”1 then today, in the world into which he entered with his family, he is surrounded by the fellowship of the saints; more precisely—the triumphant synaxis and the Church of the firstborn, which are written in heaven, and to God the Judge of all, and to the spirits of just men made perfect (Heb. 12:23). Today he truly has much more power and personal freedom.

Death clarifies many things. This is one of its functions. Thus, behind the apparent timidity of Sts. Boris and Gleb was hidden their willing sacrifice and refusal to commit fratricide. Not weakness, but strength of a special kind was soon seen in their deaths. As for the ability to fight, Sts. Boris and Gleb have manifested it from the other world—upon enemies, not upon their brothers.

Something similar has already partially happened and continues to happen with the person of the murdered Nicholas Alexandrovich and his assessment in the historical Russian consciousness. But the question does not concern only the identity of the emperor. There’s a whole range of burning questions involved in the discussion: the guilt of the people, the global deep state, the treason of the elites… Inevitability or accident? The head spins.

The Tsar was alone. Between him and the people was a dense, impenetrable layer of bureaucracy and various local authorities acting on behalf of the Tsar, but, obviously not always for the common good. “The Tsar is good, but the boyars are wolves.” This phrase can also be meaningfully said without a monarchy.

In the absence of mass communications such as we have today, the simple people saw the Tsar only in portraits in public offices and on pilgrimages (from afar). Official addresses beginning with the plural pronoun “We” only emphasized the gap between the mass of the simple people and the Tsar. A thirst for free action and personal participation in public life had already played out in the people—a thirst for news, debates, discussions, a feverish shiver in anticipation of something new. They began to apply the word “We” to themselves. They began to say “He” about the Tsar. And at the same time, among the thick and motley masses, propagandists, agitators, terrorists, and provocateurs tirelessly darted and acted across the country, quite democratically. It couldn’t continue for long.

Except for his family, the Tsar had direct communication only with his ministers and the court; and this latter and most dense circle no longer shone with faith, selflessness, and service to the crown. The Tsar’s words about treason, cowardice, and deception are precisely about this latter circle of people. Like a snake, revolution always crawls in government corridors, and only then on the streets. Image losses, systemic errors, or direct betrayals are always more easily born in the inner circle. This is more successful under a kind monarch than a suspicious and deceitful one. It is easier with a devout family man than with a gloomy ascetic or a cheerful reveler. It’s worth it to think about it, and not just think about it, but to carry the thought through to its practical conclusions.

Before becoming a bloody reality, the devious overthrow of the Tsar and the subsequent murder was prepared through information. The convoluted mind of the intellectual and the practical mind of the commoner plowed with different plows and to different depths, but both were thoroughly prepared for specific sowing. This could not be fully understood then. But now we proudly refer to the “information age.” Today, it’s impossible not to understand that information wars are a reality, as the Battle of Stalingrad and the losses in such seemingly different battles are comparable. The London printing house where “Iskra”2 was printed fully competes with the Krupp military factories3 for the production of death. It doesn’t matter that there are shells, and here is “just” paper. Before the cannons talk, the enemy fights precisely on paper.

There’s a lot to digest. The nosy journalist is more dangerous than the enemy general. An unnoticed banker in a gray suit is both more important and more terrible than a court peacock in a gold-embroidered tunic. Bankers, it turns out, can start and end wars, without consulting with kings; and the well-fed people are more easy to fool and lead to the streets under a good king than the poor and hungry under a despotic monarch. All of this is recognized from a distance.

Complex ceremonies, deep bows, and dancing on the parquet only obscure the real horror happening in people’s heads, and the specific problems in their lives. Managing the government is a heavy and daily labor, where nothing is done by itself, but everything requires attention and understanding.

Today the Tsar is with Sts. Boris and Gleb, with St. Sergius, with Blessed Ksenia, with St. Seraphim. There is neither treason nor flattery around him. He has much more power and strength. Information about the life of the Russian people is not given to him in either an intentionally or accidentally distorted form. The Tsar sees all. We rightfully await from him that blessed intervention in earthly life of which the saints are capable—and not from him alone, for the Russian regiment in the Heavenly host is innumerable—but certainly him too, for that which he could not do on earth, he is fully capable of doing now, being in the true Kingdom that cannot be moved.

Archpriest Andrei Tkachev

Translated by Jesse Dominick

1 The Tsar’s own words about his situation at the end of his reign.—O.C.

2 Meaning “Spark,” a Russian socialist émigré political newspaper established as the official organ of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party—Trans.

3 A prominent German dynasty, famous for its production of steel, artillery, ammunition, and other armaments, that played an important role in weapons development and production in both world wars—Trans.

Source: www.orthochristian.com